Humans as a Keystone Species: Design Engineers

By Allie Mason

Reading Time: ~10 min

Humans, as a keystone species?

A keystone species plays a critical role in maintaining the structure, balance, and health of an ecosystem. Its impact on the ecosystem is disproportionately large compared to its abundance or biomass. It is easy to draw the connection between the latter part of this description of a keystone species and human impact on the natural world; as for the former, to have a critical role in ecosystem flourishing, that is where perhaps we currently fall short in terms of our collective role, but it is where, as design engineers, we strive to realize our potential.

It could be all-too-easy to sink into despair, to say that the Earth would be better off without humans; however, that zero-effort conclusion is what is driving humans as a species further into an ecological role that is mis-matched for the times, for our evolutionary potential, and for the more-than-human world. Participation, even if we don’t get it right all of the time, is what will move us towards the better world we know--or at least wish--to be possible. The type of participation required for humans to be a keystone species, to self-actualize as a species, calls for deeper listening and conversing across the species boundary.

If we have the goal of becoming a keystone species that is cohesive and coherent with the more-than-human world, we could look to find a close mirror of ourselves in the environment. We could look for an animal that greatly modifies its environment to make a habitat suited for its use, or an “ecosystem engineer” of sorts. Applied in the context of design engineers and the field of hydrology, we find none other than the beaver to be an excellent example of how to restore streams, rivers, and floodplains as a result of making a place for itself. (If you’ve read any of RDE’s previous notes or examined our logo, you know we have a deep fondness for beaver.) Beaver knows how to “bend but not break” an ecosystem, and this is what we are looking to do as a species at this time of biospheric uncertainty and climate chaos. Examining beaver is an examination of how we can include ourselves in the picture of Earth’s future as a restored, resilient sphere of complex ecosystems. Beaver can also shows us that an ecosystem is not “better off without” such a key player and how removing ourselves from the greater web of life is not the answer to restoring planetary health.

Woody dams created by the American Beaver. Photography by Ronnie Howard.

In identifying key similarities and differences between how beavers engineer their environment and how humans engineer their environment, it becomes apparent where we might make shifts or changes that could take us from destructive to constructive from the perspective of a healthy ecosystem.

For example, beavers are limited to resources in their immediate environment because they are limited to “calorie-power”; humans can extract across space (trade, mining) and time (oil) and we use our calorie-power mostly as thought-workers to design technologies that amplify our access to and use of widespread resources. We rely most heavily on finite resources: we extract minerals, metals, and oil at a rate far greater than they would ever be replenished and convert them into forms that could never disintegrate back into their original forms on the planet. We take them out of the earth’s recycling process and cause degradation across time; we remove them from their original environments and cause degradation across space.

When we use materials near or on-site for stream restoration projects or living shorelines, we move closer to working with nature’s cycles and processes because of how these materials interact with the rest of the ecosystem; we also prevent negative impacts off-site by forgoing resource extraction. Instead of artificially hardening stream banks or shorelines, we support the systems in finding their way back to balance once again (after it was most likely anthropogenic factors that contributed to the original degradation of the system) through means such as beaver dam analogues for streams or natural brush materials for wave attenuation along shorelines (read more on “messy restoration” by Chris Grose here). Hand-built restoration, when the scale of a project allows, also makes installation and repair less expensive and less disruptive to the surrounding environment (such as our project at Givens Estates). It allows for the possibility of a project to be carried out as a community effort, sourcing more local hands instead of one big machine. It fosters a deeper sense of connection to place for all of those involved and serves as an opportunity for land stewardship.

Hand-built woody check dams at Givens Estate, Asheville, North Carolina

We can also consider when beaver is considered beneficial versus problematic. Beaver, like human, can be known as a nuisance in areas where their [dam-building] activities conflict with [human] land use or cause significant damage. Beaver dams can cause unwanted flooding, which may damage roads, homes, agricultural land, and other human infrastructure. They are primarily problematic in agricultural areas, where their activity can flood fields, damage crops, or disrupt irrigation systems, leading to economic losses for farmers. Outside of human disturbance, in some cases, beaver dams can disrupt the natural flow of rivers and streams, potentially harming fish populations and altering water temperatures in ways that are detrimental to certain species. As they fell trees to build their dams and lodges, this can lead to the loss of“valuable” timber, ornamental trees, or trees that provide important ecological services.

That said, the disturbance and damage to human infrastructure and agriculture occurs because of human encroachment on the floodplain, an area that would ideally be protected from development if humans were acting as a keystone species in the ecosystem. Modern-day large-scale conventional agriculture is also out of alignment with our role as a beneficial keystone species, especially in a flood plain since these methods are not compatible with seasonal flooding, unlike older methods that tolerated and were in fact designed for seasonal variation (e.g. farming in the Nile River floodplain). These conflicts reveal the deeper parallel between human and beaver and when they become problematic in the environment - that is, when they encroach on other species’ habitat and alter the environment in a way that ultimately decreases local biodiversity instead of increasing it over time, consume faster than the cycles of replenishment, and have no checks and balances with either a predator or cap on resource availability.

(Left) A section of Wash Creek flowing through Laurel Green Park before construction. This creek showed signs of erosion, with steep banks and underutilized green space. (Right) Floodplain Activation Areas after construction, they are intentionally designed to enhance habitat space, increase flood storage, and boost ecosystem services.

What is unique to humans, though, is that we have the ability, through protracted, thoughtful observation and the ability to plan and predict, to avoid destruction. Unlike beaver, who will work by instinct and a biological drive to create dams, we can choose to not follow the compulsion to develop, scale, pave, and profit. We can slow down. We can evaluate all of our options by gathering data, collaborating across space and time, and observing the bigger picture before acting.

Although it’s very much our minds that have driven us to industry, and, as a byproduct, a suffering planet and a deep disconnection with the more-than-human world, by slowing down, it’s our minds that will lead us forward to apply biomimicry and place ourselves back within the greater web of life. It’s our minds that can make us once again a keystone species.

Allie and Amy at the annual RDE retreat amongst coworkers rudbeckia, purple aster, sweetgum, sourwood, and eastern red cedar.

Laurel Green Park and playground reopens after year-long stream restoration

In 2019, the Town of Laurel Park commissioned Robinson Design Engineers to create a watershed masterplan for the community. The Town’s gateway is Laurel Green, a creekside park with a popular playground and walking trails and connectivity to the Ecusta Trail.

In 2020, the Town was awarded a grant by the North Carolina Land and Water Fund to naturalize the creek flowing through Laurel Green and expand its floodplain. This tributary, which flows for approximately 780 linear feet through the park, joins Wash Creek near the downstream end of the park and eventually flows into Mud Creek in downtown Hendersonville. Long ago, the creek was channelized, forcing the natural stream into a straight channel and mowed banks. In recent years the creek banks actively eroded and the stream bed shifted and migrated, contributing to sedimentation in Wash Creek and Mud Creek and threatening infrastructure along the creek corridor.

Community members traverse the floodplain activation wetlands through the new trail and boardwalk system.

For the last few years we’ve worked closely with the Town, Watermark Landscape Architecture, community members, and funding partners to design, permit, and build the creek restoration and floodplain activation project. And in May of this year, after nearly a year of construction, the park has reopened. We were excited to share the project with local, regional, and state partners—and with our friends and families.

A new boardwalk overlooks the stream corridor while allowing floodwaters to pass beneath the trail and into lateral floodplain wetlands.

Read more about the project in this article by the Times-News.

The Few, the Proud, the Marines and Volunteers Who Built a Living Shoreline

In 2022, The Nature Conservancy of South Carolina engaged Robinson Design Engineers to provide design and permitting support for 2,000 feet of living shoreline along the Broad River in Beaufort, SC. The project is located in the Laurel Bay community of Port Royal Island, part of the Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort.

Volunteers building an oyster castle living shoreline reef near Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort (Photo: Lance Cpl. Kyle Baskin/U.S. Marine Corps, via NOAA Fisheries)

The goal of the project is to protect a segment shoreline that has been eroding due to persistent boat wake and to foster the regrowth of a natural oyster reef and intertidal marsh vegetation. The project was supported with grant funding by the NOAA Office of Habitat Conservation, and constructed by volunteers from the local community, DoD personnel, and the Sustainability Institute’s Environmental Conservation Corps—who worked to place nearly 42,000 Oyster Castles — a proprietary living shoreline system of interlocking concrete blocks. One of the first living shoreline projects permitted along the South Carolina coast, the project was technically challenging and required close coordination with the project sponsor, state and federal permitting officials, and Department of Defense staff.

Illustration of Oyster Castle living shoreline by Robinson Design Engineers.

This project is helping The Nature Conservancy and other partners to expand its community assistance program to build living shorelines along the properties of residents in historically marginalized coastal communities, including within the Gullah Geechee Natural Heritage Area.

Read more in this Feature Story by NOAA Fisheries or in this article by the Post & Courier.

Goodbye, turf grass

For the last several years, RDE has worked with the neighborhood association at Seaside Farms in Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, to improve the health and function of their network of stormwater ponds. As part of the first phase of rehabilitating the ponds, several thousand feet of eroding shorelines were graded, stabilized, and planted with a buffer of native plants by the Shoreline Restoration Group.

The Post & Courier recently featured this work on the front page!

To stabilize the eroding pond shorelines, RDE recommended a combination of hand-grading, coir matting, and coir logs, and an intensive planting scheme along the entire HOA-controlled buffer zone. To foster a diverse, functional, and beautiful shoreline, RDE defined three distinct planting zones based upon modeled water levels in the pond system during various storm events: Emergent Zone, Riparian

Shoreline planting schematic by RDE

In Search for Flooding Solutions, Conway Looked to Carolina Bays

Greenville Business Magazine recently featured an article about Chestnut Bay, a flood management project that Robinson Design Engineers conceptualized in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy of South Carolina and the City of Conway. RDE is currently leading the design and permitting of Chestnut Bay, with collaborative design support from Bolton & Menk, Biohabitats, and The Brigman Company.

Conceptual rendering of Chestnut Bay by Lucy Rummler.

Troubled waters: South Carolina's oldest stormwater ponds exist in regulatory 'no-man's land'

Joshua Robinson recently spoke with Jonah Chester at the Post & Courier about the challenges and opportunities of stormwater ponds in the Lowcountry. Here are some excerpts from the article, which can be read in full here.

Stormwater ponds, especially older ones, can become a soup of chemical and biological contamination. Yard fertilizer, pond-cleaningchemicals, trash and oil are just a few of the pollutants that can accumulate in a pond over time. When a large storm or hurricane hits,pollutants that have settled at the bottom of the pond can become resuspended and potentially wash out into the landscape, eventuallymaking their way to natural waterways.

“These ponds are becoming similar to wastewater treatment plants because they’re accumulating so much old material, and there’s no plan for what to do, other than it’s up to the owner of the pond to make sure that they’re in good working order,” Robinson said…

While some stormwater ponds may pose a growing environmental threat, they’re also “low-hanging fruit” for wetland restoration, Robinson said. Many are located in areas that were originally wetlands, and he said rehabilitating them with natural plant-life can filter water and create new habitats for local wildlife. “If we don’t plant native vegetation that we want to clean the water, then undesirable vegetation is going to grow,” he said. “If we don’t treat the pond like an ecosystem, and actually nourish the good parts of it, then eventually the only organisms that can live there are the extremely pollution-tolerant organisms.”

CHS 2030: Nurturing Our Urban Creeks

Joshua Robinson recently sat down with our friend Belvin Olasov, co-director of the Charleston Climate Coalition, to talk about possibilities for an aspirational, eco-futurist vision for the Lowcountry. The conversation and the article it inspired in Surge Magazine centered on Gadsden Creek, and how community efforts to preserve and reviatlize the historic tidal creek could serve as a blueprint for Charleston’s emerging relationship to water.

1954, Gadsden Creek being filled with municipal waste. Photo credit: Post & Courier

Laurel Green Park closed for stream restoration project

Quoting the Hendersonville Lighting:

LAUREL PARK — Laurel Green Park will be closed starting next week for a stream restoration project along Laurel Green Creek and Wash Creek, a total of about a quarter mile.

The project includes tree and brush removal, site grading and channel stabilization, floodplain activation areas, and stormwater improvement, trail and boardwalk construction and landscaping.

Laurel Park is collaborating with the North Carolina Land and Water Fund and the North Carolina Department of Public Safety to fund the project, which was designed by Robinson Design Engineers and Watermark Landscape Architecture, Land Planning, and Consulting.

RDE Creek Daylighting Projects Featured on SCETV Palmetto Scene

The SC ETV show Palmetto Scene recently featured Hyatt Park and Smith Branch as part of their SC Stories series. Watch the show here; the segment on stream restoration begins around minute 15:00.

The episode includes interviews with several of our friends and collaborators from the City of Columbia: Warren Hankinson, Watershed Coordinator; Todd Martin, Park Planner and Project Manager of the Hyatt Park renovation project; and Karen Kustafik, Assistant Park Superintendent.

Messy Restoration

By Chris Grose

Fueled by the good intentions of the regulatory sector and the financial incentives of compensatory mitigation, the aquatic restoration arena attracts engineers, consultants, landscape architects, contractors, and financial managers. There is little doubt that much of the restoration work being performed is generally beneficial. However, are we hindering the potential for true restoration by limiting our thinking and methodologies to fit into a regulatory framework designed for checklists and scores?

The extreme hydraulic forces imposed by the urban watershed, coupled with many physical and regulatory constraints, required that RDE design the new stream bed of Smith Branch to be robust, static, and organized by a sine-generated curve

Boulder weir, typical of the flow diversion structures favored by many regulators and resource agencies for the fish habitat they create. Designed by others, photo credit unknown.

As the farmer-poet Wendell Berry wrote, “We have never known what we were doing because we have never known what we were undoing. We cannot know what we are doing until we know what nature would be doing if we were doing nothing" (from Preserving Wildness). Natural processes gradually restore impaired systems to a more functional state. If we did nothing, what would nature do to restore our riverine ecosystems? Would it be the few geomorphic forms that have become synonymous with stream restoration, e.g., single-thread channels with riffle-pool sequences? These certainly have their place, but streams undisturbed by man (although arguably non-existent) are not the nice, tidy channels we like to see in our minds eye. Nature finds organization in the messiness of chaos.

Nature-based solutions, such as beaver dam analogues and engineered woody jams, are attempts to mimic this messiness. They are inherently resilient structures not because of their permanence but because of their plasticity. Unfortunately, this plasticity contradicts the currently accepted philosophy of stream restoration, which strives to construct a channel that is geomorphically immutable, satisfying some performance standard rubric in perpetuity. The difficulty in garnering acceptance for nature-based solutions over the current state-of-practice approaches is not because the former represents a flawed approach but rather because nature-based solutions do not fit nicely into the regulatory framework.

With few site constraints in the newly renovated Hyatt Park, the City of Columbia offered RDE the freedom to design woody jams within a messy creek corridor.

Beaver Dam Analogue by WildEarth guardians

In their defense, regulators have the unenviable job of authorizing and monitoring the sale of restoration credits for financial gain. Their struggle is how to keep the playing field even and ensure that those performing the projects place ecological goals above economic ones. Messy restoration, no matter how imitative of nature it may be, simply does not work within this contrived system of approvals and monitoring. Nature-based solutions change over time, sometimes often and drastically, and as a result, defy attempts at objective assessment. This propensity to change and create resiliency seldom allows for “one-size-fits-all” rule-making. The real challenge for restoration professionals is not to prove that nature-based solutions are worthwhile and historically present in nature, but rather to create new ways to allow the regulatory community to embrace the mess.

Beaver Moon

By Rebecca Fanning

This time last year, while enjoying a brief respite between thesis writing and thesis defense, I was in attendance at Robinson Design Engineers’ annual retreat under the Beaver Moon. I’ve had the honor of attending two RDE retreats, bookends of a graduate research internship. The first year I took part, our campfire was visited by none other than the American beaver, (Castor canadensis), documented in the photograph below under Nolan Williams’ headlamp. Remarkable it should have found us, since RDE had recently adopted its image as a secondary logo – a creative license that designer Jay Fletcher made without one word from any of us as to the significance of this creature to RDE’s work.

A visitor at RDE’s retreat | Image: Nolan Williams

RDE logo featuring C. canadensis by Jay Fletcher

It is perhaps ironic to some that water resource engineers like RDE would proudly bear this emblem: a tree, a mountain stream, and a beaver in the middle. Widely considered a nuisance pest, beavers fell trees, plug culverts, convert rushing water to sluggish wetland meadows, flooding all sorts of critical infrastructure, and for centuries they have evaded the United States’ best efforts at extirpation.

The beaver’s innate anxiety at the sound of rushing water and all the industrious efforts it has taken over generations to slow the flow of water offers a lesson us humans should adapt to adopt. Formerly ubiquitous beaver dams, small and large, created frequent and chaotic natural disturbance regimes that native plants and animals have coevolved to depend on. Should a critical piece of a beaver dam break off in a flood, compromising the structural integrity of the whole, the diligent caretakers rush in to repair, shore up, and reduce the risk of future failures by building in an upstream direction, creating resilient cascading systems of distributed water management. The construction activities of beaver are as flexible as the materials they use and are forever a work in progress. The Beaver Moon reminds us that to live with water, we must change the way we live, and we must work at it with considerable forbearance.

Last Beaver Moon, my graduate degree coursework at the College of Charleston was being conducted exclusively online, and so, too, were thesis defense presentations. Knowing how it feels to give a one-hour talk to a mute, virtual room, my sympathetic research colleagues determined that the annual RDE retreat would commence loudly. I was surprised by a carol of sorts to the tune of Sounds of Silence, with words chock full of inside jokes, interrupted by uncontrollable laughter, and culminating in a toast to my recent accomplishment of “10,000 pages maybe more”. As grateful as I felt then and feel now for the opportunity to work with and learn from these fine folks, I received their own sincere gratitude in response for the research I did and the insights I brought to them. The process of transformation was reciprocal, and the graduate degree I obtained was a shallow watermark compared to the flood of information I researched with RDE’s help.

What I investigated, wrote, and later presented, Legacies & Trajectories to Inform Piedmont Stream Restoration, was in service to one of RDE’s trickier project sites: a small watershed in the Piedmont of South Carolina, now held in conservation easement, that is torn apart by deep gullies and crisscrossed by old logging roads and ATV trails. What RDE proposes to do to restore the streams of this site remains unprecedented in the state of South Carolina. Their design mimics the work of the Carolina beaver (Castor canadensis carolinensis), and tempers stream power and erosive flows with simple, messy log structures, a far cry from the designs promoted by the National Engineering Handbook 654 for stream restoration. Essentially, RDE took the work of the beaver and gave it an official engineer’s stamp of expert approval. You’ll have to stay tuned for what comes from this approach.

What better occasion than a Beaver Moon for RDE’s retreat to assess the past year's work and make adjustments for the year ahead? Like a series of beaver dams bolstered in an upstream direction, RDE's work is never complete. This Beaver Moon, I encourage you not to submit to small failures, but to assume responsibility for what is within your power to change. And change it.

The Beaver Moon | Image: jplenio

All Hail the King [Tide]

By Emma Collins

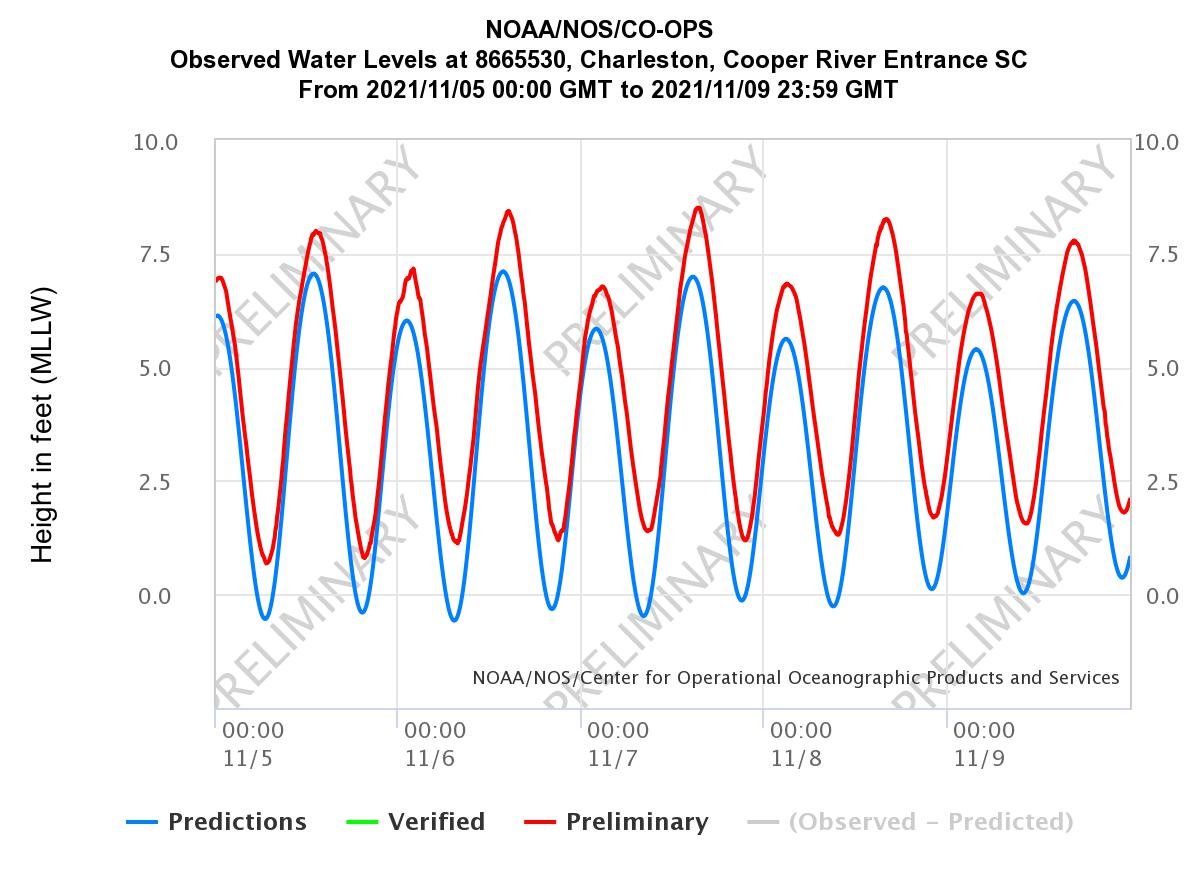

Last Sunday (November 7, 2021), Charleston experienced the 10th highest tidal crest on record. Annual tide charts have warned for months that a King Tide would occur this past weekend, just as they’ve predicted the handful of King Tides that occur every year. So what made the November 7th tide special, finding a place in the top 10 of a list normally reserved for hurricane storm surges?

Flooding in North Charleston during Sunday’s King Tide | Photo: Matt Woods

A King Tide is a non-scientific term referring to an exceptionally high tide. King Tides are sometimes considered synonymous to the perigean spring tide, when the moon and sun align with the Earth, and the moon is at its nearest point in its elliptical orbit. (More on the science behind that here.) When a King Tide occurs, we’d expect the coastline to experience an extremely high tidal range, meaning the high tide is higher than usual, and the low tide is lower than usual. Nuisance flooding may occur in low lying areas due to a King Tide alone, but the major coastal flooding that occurred this past weekend was not due solely to an extreme tidal range.

This weekend, a storm system off the coast invoked strong onshore winds and changes in barometric pressure, resulting in higher high tides. When coastal storms coincide with a King Tide, the higher high tide can become even more exacerbated by these storm effects. It is of note that this does not necessarily mean the tidal range will be greater, since low tides are also likely to be higher than normal. We might see the same effect if a King Tide were to coincide with a large storm blowing in from the west, when our waterways are already full of rainfall-runoff. We keep an eye out for King Tides, not because a King Tide alone will cause major flooding, but because it can amplify any other flooding sources. The moon and sun’s gravitational tide-causing forces are unlikely to change in the foreseeable future, but sea level rise and increasingly frequent extreme weather events make the King Tide a growing threat to coastal areas.

Hydrograph from the Charleston Harbor gage showing higher high tides and higher low tides than predicted | Image: NOAA

Giant Salamanders

By Philip Ellis

I’ve been paddling and hiking in creeks and rivers my whole life. When I was young, I found amphibians to be the most interesting wetland creatures, and this held particularly true for salamanders — they are oddly charismatic in their small and slimy way. This is why, in my adult life, I was amazed to discover that a giant version of these animals existed: The Eastern Hellbender. And more exciting to me was that the Hellbender’s habitat is in clean mountain creeks of Southern Appalachia. Thus began my 14-year search.

Even if you spend a lot of time in mountain streams, Hellbender sightings are rare, especially for an impatient whitewater enthusiast like me. It seems that the slower and more methodical explorer has a higher chance of encountering these shy little dragons.

Tropical storm Fred brought a torrential downpour onto the Balsam Mountains in August of 2021, causing floods and extensive damage to towns like Canton and Rosman, NC. After this flood event, I was paddling on the North Fork of the French Broad River. It was there, in-between two classic rapids (Boxcar Falls and Diagraslide) that I stumbled across this 18-inch-long beauty. The giant salamander was clinging to the gorge wall, blending in spectacularly. I stepped over it a couple times before looking down and jolting with joy at the sighting.

This sighting was even more impressive because of the destruction from the Fred-induced flood: boulders had moved, bedrock was scoured clean, a waterfall (Submarine Falls) had collapsed and propagated upstream a few dozen feet, and the storm even mobilized some old steel rail from the floodplain (this steel rail was left from logging operations over 100 years ago). Seeing these massive geomorphic changes to the creek made it clear that Hellbender habitat was also disrupted. Even though tropical storms are a natural occurrence, it is hard to imagine such a finicky species surviving a flood because Hellbenders tend to live in clean cobble-bed streams using larger boulders for refuge. Nonetheless, there it was, resting on the side of the gorge, waiting for the water to recede, and waiting for me to stop gawking.

Shallow, clear rocky streams in western North Carolina like this one are prime habitat for Eastern Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis)

Paddling Submarine Falls

The Statistics Behind the 100-Year Storm

By Emma Collins

If you live in a flood-prone region, you probably hear a lot about something called the “100-year storm.” But what is that exactly?

Flooding in Conway, SC after hurricane Florence (Jason Lee/Sun News/AP)

What is the 100-year storm?

The 100-year storm is the number of inches of rainfall one could expect to occur in a certain period of time (usually 24 hours) with a 1% probability any given year. Note that this is not the same as the 100-year flood, which is the water surface elevation that one could expect to experience with a 1% probability in any given year. This is a theoretical number derived from years of observed data, and while a common misconception is that a precipitation event of this magnitude is a once-in-a-hundred-year storm, it’s better to think in terms of probability. A 1% annual probability does in fact mean that the 100-year storm will occur once in a span of 100 years on average, but this is often erroneously presented as an event that will happen at most once every 100 years.

For example, the 100-year rain event for Charleston, SC, is 10.2 inches in 24 hours. The historic weather events in October of 2015 brought 11.50 inches of rainfall in 24 hours to the Charleston area, but the 100-year storm event was also exceeded in September of 1998, when Charleston experienced 10.52 inches in a day. So, what happened? Is it a fluke that in a span of 17 years a city could have two storms that exceed the 100-year rainfall? Statistically speaking, this shouldn’t be a huge surprise. There is a 15.7% chance that a 100-year event will occur at least once in a 17-year period. More specifically, the probability that the 100-year storm will occur at least once is as follows:

How well does this number represent reality?

This is a highly debated question. In most cases, the 100-year event is either extrapolated from a dataset covering less than 100 years, or taken from a dataset of around 100 years. The underlying assumption of this type of analysis is temporal stationarity, which is to say, rainfall patterns will not change throughout time. If extreme weather events start to occur with greater frequency, then using historical weather data to predict future weather data will not be possible. It would be more accurate to represent the 100-year storm as a storm that has historically occurred once in a span of 100 years on average.

What this means for Stormwater Management

Urban areas often struggle during unusually large storm events. Relative to rural areas, cities are usually characterized by high amounts of impervious surface (i.e. area in which rainfall cannot soak in to the ground). This means that during storms most precipitation gets directed into gutters and sewer drains, which for large enough events can overwhelm a city’s stormwater system, backing up ditches, storm drains and culverts. This is especially a concern in areas that are experiencing rapid development. Many stormwater systems are designed to handle a 100-year storm’s worth of runoff based on the amount of impervious cover, but that may become overwhelmed in a 10-year storm if new development converts formerly vegetated area to impervious surface (such as rooftops and pavement). Likewise, if changing climate patterns were to cause the formerly 10% annual probability storm to occur with a 50% annual probability, the stormwater system in place would quickly become insufficient.

While stormwater systems can be engineered to handle any amount of flow, there is a point of functional and economical diminishing return. Municipal systems generally aren’t built to withstand the 1000-year flow because even though the impact can be catastrophic, they are statistically unlikely to occur. However, in the event large volumes of runoff become increasingly common, stormwater systems must be designed to accommodate the moving point of catastrophe.

Charleston City Council Adopts the City Plan

The 2020 Charleston City Plan is the most recent comprehensive plan for the City of Charleston. Revised every ten years, the 2020 Plan includes a detailed Land & Water Analysis.

Working as part of the Waggonner & Ball team, Robinson Design Engineers prepared recommendations and design guidelines for Water Management Measures for the various landscape types contained in the city bounds.

Welcome, Amy!

Amy Nguyen is joining RDE as an intern, bringing with her a foundation in geological sciences, a deep understanding of urban flood adaptation, and impressive visual communication skills! She earned a bachelor’s degree in geology from Clemson and just wrapped up her Master’s in Resilient Urban Design, a Clemson University program that uses Charleston as its living laboratory. Amy previously interned as a Design Fellow for The Riley Center for Livable Communities and as a Keeping History Above Water (KHAW) intern for The Newport Restoration Foundation, advancing her skills in graphic design, community engagement processes, and stakeholder collaboration. We are lucky to have Amy working with us!

A map from Amy’s graduate project Designing with Water

Breaking ground on Hamlet vernal pool

Excerpt

Chris Grose and the crew of The Hamlet, a cottage community in Flat Rock, were out in the cold breaking ground on a vernal pool. These wetland features experience seasonal drying and shallow flooding that prevents establishment of fish populations, making them critical breeding areas for amphibians predated by fish. Some amphibian species - such as spotted salamanders, marbled salamanders, and wood frogs - must migrate to a vernal pool each spring in order to breed, but many of these pools are lost to development.

This vernal pool project was made possible by a conscientious neighborhood developer, who wanted a trail system that allowed residents to enjoy nearby natural features. The trail system (designed by Osgood Landscape Architecture) loops around former farmland along Dunn Creek

The pool will change with the seasons and become an even more interesting stop on the trail as the plants mature and amphibians, birds, and insects find their way to this habitat. We hope residents enjoy blooms and sounds of spring peepers here for years to come!

Charleston area lost more than 10,000 acres of tree cover since 1992, making floods worse

Joshua Robinson recently spoke with Tony Bartelme, senior projects reporter for the Post & Courier, about the importance of trees to the hydrology of the Lowcountry landscape. The resulting article, part of the Rising Waters special reporting series, discusses the flooding of Crosstowne Church and RDE’s work on behalf of the church.

Paul Rienzo is pastor of Crosstowne Church. Bostonian by birth, he moved to Charleston 37 years ago. His church sits in a dip off Bees Ferry Road, not far from Church Creek. Though it's in a low spot, he thought it was safe from flooding. “It didn’t even flood in Hugo,” he said.

But in 2015, the remnants of Hurricane Joaquin brought a lumbering storm, one that dumped 2 feet of rain on Charleston and Mount Pleasant. Off Bees Ferry Road, floodwaters poured into the church. Rienzo grabbed his kayak and paddled inside to save the sound equipment. At the time, then-Gov. Nikki Haley called it “a thousand-year storm.” But floods came again in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Rienzo wondered why it was happening so often. Was it just chance? “Something had changed,” Rienzo said. The church hired their own hydrologists and engineers, who made a startling discovery.

Joshua Robinson was lead investigator. He runs Robinson Design Engineers in Charleston and Asheville and teaches at the College of Charleston. Their first priority was to get a better handle on the area’s hydrology — how Bear Swamp collected and released water. And they found clues in a nearby forest.

The U.S. Forest Service had done extensive research in the Francis Marion National Forest, the bulwark of green north of Mount Pleasant. Robinson had assumed that when rain fell in the forest, stormwater flowed out via its many creeks and rivers. But Forest Service scientists found something else was going on.

In this flat landscape, about 70 percent went back up into the skies, mostly through the forest's trees. “It seems so obvious," Robinson said in retrospect. "You look at one fully grown tree and how much water it needs.”

In a low-lying area, forests and wetlands had evolved into highly efficient pumps. Pines and oaks and cypresses pumped water from the ground through their roots, which allowed even more water to enter the soil and drain faster. Then the forests released the water through their leaves and needles in a process called evapotranspiration. With their many needles, pine trees were especially efficient water collectors.

Robinson was amazed: “Forests return 7 out of every 10 inches of rain to the atmosphere.”

But as Robinson and his colleagues studied changes in Bear Swamp, they saw how developers and governments had built ditches to guide stormwater toward the Ashley River, and ultimately, the Atlantic. Water flowed faster through the basin. These growing pulses of water overwhelmed ditches and Church Creek. At the same time, some of the ditching allowed tidal water from the Ashley River to flow inland.

“This landscape and its soils formed over eons, and then in a small timescale, a matter of decades, it was turned into rooftops, pavement, more ditches," Robinson said. Area governments had allowed this development "without an awareness — or the tools to understand the power of these actions.”

For Robinson, it was a eureka moment: The Lowcountry's forests and wetlands were amazing pumps; if you got rid of them, stormwater flowed faster through the area. Flooding got worse, requiring more ditches and pipes, a cycle of failure.

He finished the study thinking that the forests and wetlands in Church Creek Basin and elsewhere "should be preserved at all costs.”

Cover photo by Post & Courier. Read the full article here.

From Former Mental Hospital to Recreational Hub

Since 2014, RDE has worked with the Hughes Development Corporation and the City of Columbia, SC to naturalize and “daylight” Smith Branch, a creek that flows through the site of the historic state mental hospital. Quoting from a recent article about the project in the New York Times:

Sean Rayford for The New York Times

The South Carolina Lunatic Asylum admitted its first patient in 1828. Ever since, its impressive brick wards surrounded by nearly 200 acres of leafy lawns and gardens served as landmarks in Columbia, the state’s capital.

Almost 200 years later, and three decades after the last patient was discharged, the old brick buildings and expansive open space are being steadily converted into one of the largest downtown mixed-use real estate projects in the nation, a 181-acre development known as the BullStreet District…

More than $100 million has been invested to construct an inviting downtown destination that Columbia has never had before. BullStreet is steadily emerging as the civic space that Stephen K. Benjamin, the city’s three-term mayor, envisioned when he persuaded the City Council in 2013 to begin collaborating on the project with the Hughes Development Corporation, a developer based 100 miles away in Greenville…

Hughes is also constructing a $4 million, 20-acre park, which features restoring the natural flow of Smith Branch, a tributary of the Broad River that runs through the site. Before Hughes took ownership of the development, the creek flowed for 1,000 feet above ground, and then disappeared for 1,600 more feet into two mammoth underground concrete pipes the state installed in the 1950s to control flooding.

“Joshua Robinson, an engineer and hydrologist from Charleston, designed a restoration plan to clear the first 1,000 feet of debris and rebuild the existing channel. He then constructed 1,600 feet of new channel on the surface, freeing the creek from the pipes. Mr. Robinson did not demolish the old pipes, though. He left them in place and built a concrete weir, a compact dam structure that during storms diverts high flows into the pipes and protects the park from floods.

“The stream is the spine of the park,” said Mr. Robinson, who expects to open the park later this year. Upstream will be the most naturalistic part of the park with native vegetation. Downstream will have manicured fields and walking paths, a two-acre pond, pools and shade trees. “It will be a diverse experience, feel natural, and all in human scale,” he said.

Givens Estates completes its innovative stormwater project

Since 2008, RDE has provided consulting, planning, and design services to Givens Estates, 200-acre United Methodist Retirement Community in Asheville. We first led a campus-wide masterplanning effort that includes a prioritized schedule of projects, capital improvements, and housekeeping measures to reduce stormwater flooding, improve the quality of the three mountain streams flowing through the campus, and strengthen the institutional efforts toward ecological restoration throughout the campus.

In 2016, Givens and local non-profit RiverLink were awarded an Innovative Stormwater Management grant from the NC Clean Water Management Trust Fund. RDE collaborated with RiverLink to submit the grant, providing the technical data and supporting information. We recently completed construction of the project; the press release by RiverLink was published by Mountain Xpress and is included below.

In-stream structures, built by hand with logs and stones, slow high velocity flow and prevent pollutant sediment from flowing downstream to Dingle Creek and the French Broad River.

Press release from RiverLink:

Construction is now complete on the Givens Estates Innovative Stormwater Project. Funded by a $166,975 grant from the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, in conjunction with $359,468 in matching funds from Givens Estates and RiverLink, the project constructed retrofits to six stormwater control measures (SCMs) on the Givens Estates campus, a Methodist retirement community in South Asheville.

The SCMs will capture runoff from Givens Estates, preventing sediment from entering Dingle Creek, a major tributary to the French Broad River. Sediment—the number one pollutant in the French Broad River—is a priority for RiverLink due to its ability to carry pollutants throughout the watershed and harm aquatic organisms such as fish and the threatened hellbender salamander.

The innovative aspect of the project is the research being conducted by RiverLink and Robinson Design Engineers to determine how effective the SCMs are at capturing sediment. The majority of stormwater research in North Carolina has occurred in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions. The results of this study will help set the design standards for stormwater control measures in the steep slopes of Western North Carolina. Preliminary data is promising, with 4.5 tons of sediment captured by the SCMs in the first post-construction rain event.

The project was a collaborative effort with Robinson Design Engineers providing design and research services, NC State University Minerals Lab offering in-kind donation of sediment sample analysis, and Miller Brothers Inc providing construction services. In addition, 633 hours of community service was provided by RiverLink volunteers and 710 native plants were installed in the SCMs.

RiverLink’s Watershed Resources Program works to improve water quality and quantity within the French Broad River watershed in Western North Carolina. The program utilizes a multi-faceted approach including grant-funded projects that mitigate stormwater runoff, restore degraded aquatic and riparian habitats, and create watershed plans, along with education initiatives that raise awareness and empower citizens to improve regional water quality.

Since 1987 RiverLink has worked with local citizens, community leaders and businesses to address the environmental and economic health of the French Broad River Basin. The organization is a key player in revitalizing the riverfront district, providing recreational and educational amenities for citizens and visitors, and promoting conservation and environmental education initiatives.

For more information on the Givens Estates Project contact:

Renee Fortner, Watershed Resources Manager renee@riverlink.org (828) 252-8474 X 14.

For general information about RiverLink, including upcoming events, projects, and ways to give visit www.riverlink.org.

![All Hail the King [Tide]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60e5d78119a4801e13145927/1636649445499-SJVQF1LFO0ED36JH8UNQ/Photo+Nov+07%2C+11+39+34+AM.16-9+ratio.jpg)