All Hail the King [Tide]

By Emma Collins

Last Sunday (November 7, 2021), Charleston experienced the 10th highest tidal crest on record. Annual tide charts have warned for months that a King Tide would occur this past weekend, just as they’ve predicted the handful of King Tides that occur every year. So what made the November 7th tide special, finding a place in the top 10 of a list normally reserved for hurricane storm surges?

Flooding in North Charleston during Sunday’s King Tide | Photo: Matt Woods

A King Tide is a non-scientific term referring to an exceptionally high tide. King Tides are sometimes considered synonymous to the perigean spring tide, when the moon and sun align with the Earth, and the moon is at its nearest point in its elliptical orbit. (More on the science behind that here.) When a King Tide occurs, we’d expect the coastline to experience an extremely high tidal range, meaning the high tide is higher than usual, and the low tide is lower than usual. Nuisance flooding may occur in low lying areas due to a King Tide alone, but the major coastal flooding that occurred this past weekend was not due solely to an extreme tidal range.

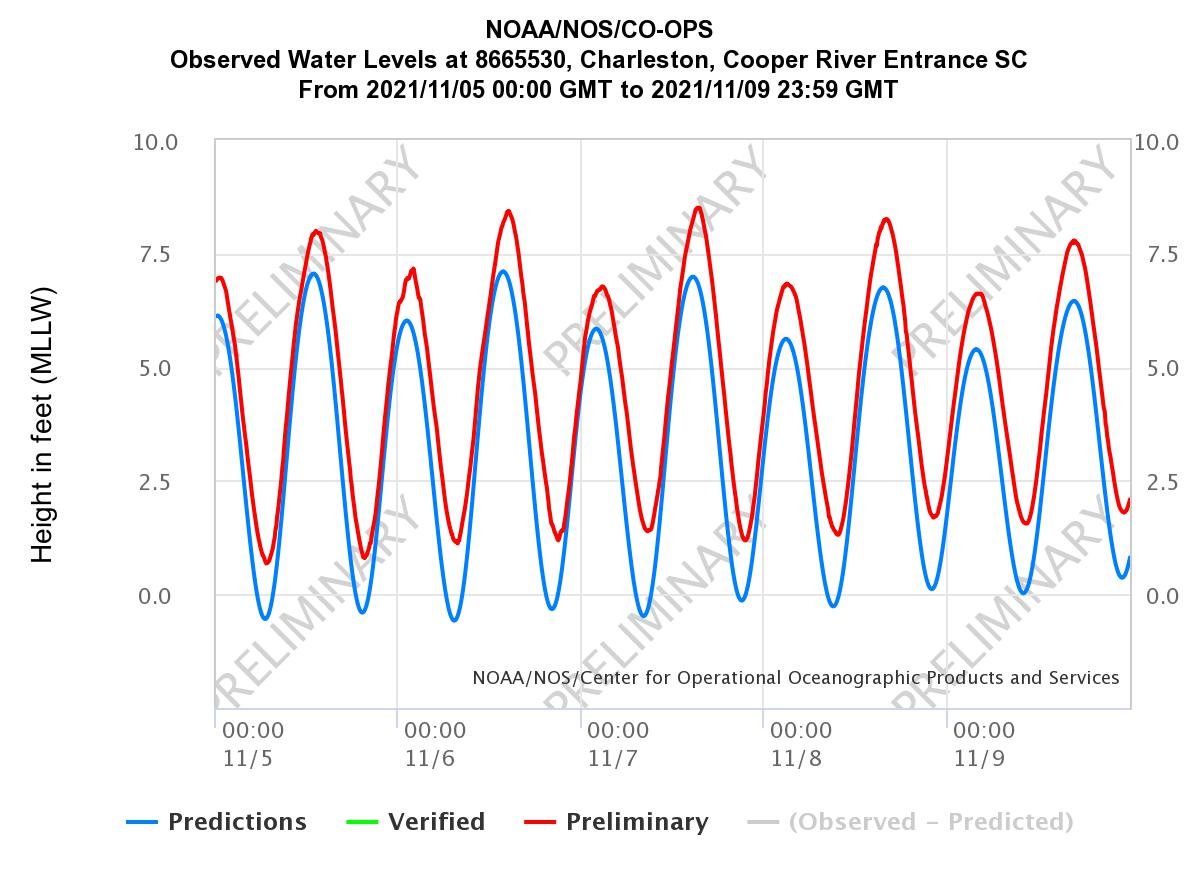

This weekend, a storm system off the coast invoked strong onshore winds and changes in barometric pressure, resulting in higher high tides. When coastal storms coincide with a King Tide, the higher high tide can become even more exacerbated by these storm effects. It is of note that this does not necessarily mean the tidal range will be greater, since low tides are also likely to be higher than normal. We might see the same effect if a King Tide were to coincide with a large storm blowing in from the west, when our waterways are already full of rainfall-runoff. We keep an eye out for King Tides, not because a King Tide alone will cause major flooding, but because it can amplify any other flooding sources. The moon and sun’s gravitational tide-causing forces are unlikely to change in the foreseeable future, but sea level rise and increasingly frequent extreme weather events make the King Tide a growing threat to coastal areas.

Hydrograph from the Charleston Harbor gage showing higher high tides and higher low tides than predicted | Image: NOAA